Les Woodland Takes His Bike to Vietnam

Les Woodland Takes His Bike to Vietnam

If anyone has the right to sing Johnny Cash's "I've Been Everywhere", it's cycling writer Les Woodland. I think the only continent he hasn't visited with his bike is Antarctica.

If you enjoy this piece, I know you'll love his book about his trip by bike across the U.S., "Sticky Buns Across America: Back-roads biking from sea to shining sea". Just click on the cover art to the right to get your print, Kindle or audiobook copy.

Les has been writing about bike racing for decades. The Tour de France, Paris-Roubaix, Tour of Flanders, The World Championships? Les has written insightful books about these iconic races. They are filled with wonderful, largely unknown tales. He gives the inside story.

Most of Les' Books are available in print, Kindle eBook and audiobook versions.

Click here to go to Les' Amazon author page

Les Woodland rides on a busy Vietnamese highway at rush hour

You know something I notice when I go to America? That nobody wears Vietnamese army uniforms.

That would pass as unremarkable were it not that Vietnamese lads wear American uniforms. Not many of them, naturally, but it's remarkable that any do at all. Not army surplus, either, or blood-stained and bullet-holed, but new clothes, bought in shops, with bright "US Army" patches.

Visit a market and you'll find copies of US kitbags, stencilled and printed in camouflage swirls.

Why? I've no idea.

But then a lot puzzles me about Vietnam. After two months of cycling there, largely from Hanoi south to Saigon, we have as many questions as answers.

Over and over we were stopped for photos, asked our names and - no social stigma - how old we were. We were in the backwoods, of course, and none of this happens on the highways or in cities, where westerners are common. We'd ride through villages on roads two meters wide and lined by people squatting outside houses as they peeled vegetables or mended motorbikes or whatever else they were up to.

And sometimes the road disappeared completely

And we'd ride through a tidal wave of delighted shouts, waves and then giggles. Those two meters ahead would spot us and set off the next people and so it would go on for a kilometer or more.

So you have this enormous friendliness, care, happiness to meet strangers. And then, as you walk through town, someone will park a scooter across your path, just where you were about to put your foot. Try to escape into a café and you'll fight through parked scooters and motorbikes, because nobody thinks to leave a passage to the entrance. You just park where you like, whoever else is there or could want to be there. It's a symbol for the way life is lived, of local customs. We find it odd, thoughtless and foolish, but there it's just life. It's we in their land, not the other way round.

And so it is with the Vietnam war, or the American war as it's known there. To be honest, you'd think it never happened. In Vietnam, it's history. There'll be war bores who'll relate every metre gained, and maybe some prickle between the communist north and the overturned south (you'll notice that it was Saigon, capital of the south, that was renamed Ho Chi Minh City, not Hanoi in the north), but generally people don't care.

A land of stunning beauty

It's Americans who go back, tourists who visit the tunnels outside Saigon, the refuge caves of the coast and what remains of airfields. The Vietnamese can't work out why, especially the Americans. They lost; why would they want to reopen the wounds?

And yet, and yet...

There are two highways that run most of the length of the country. One is Highway 1, which spreads noisily along the coastal plain. And the other is through the low mountains amid the best scenery that Vietnam offers.

We'd planned to ride this inland road, one cyclists ignore in its northern reaches for its hilliness and scarcity of accommodation and food. We didn't in the end because Steph tripped early in the trip and ricked her wrist enough that pulling on the bars or braking hard ruled out three-dimensional riding.

But the point is that this road, uniquely in Vietnam, has yellow lines down the middle. Everywhere else has white lines.

Any why yellow lines? Because this is the trail, now surfaced and much widened, on which soldiers from the north carried guns, bullets and supplies on their shoulders to the battlefront further south. It took the Americans a long time to work out that supplies were creeping beneath the canopy of the mountain forest. And their answer was to douse the entire area in Agent Orange, a spectacularly poisonous herbicide.

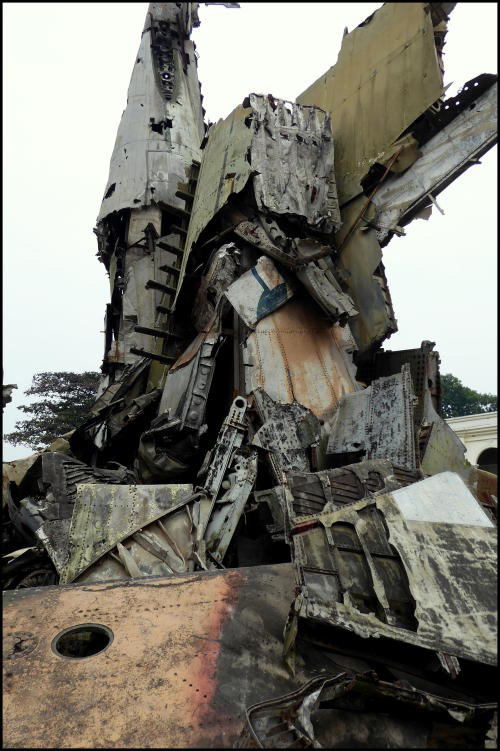

How many lives ended on both sides? The remains of American jets

It destroyed not just the forest but surrounding farms (which have never wholly recovered)... and lives.

And that, the Vietnamese are bitter about. The poison passes down through the genes and causes horrible deformities. Twice, we visited workshops established by the government to give gentle work to victims. There are still a great many.

And so we rode not the Ho Chi Minh or Highway 1 but tiny roads that more than once turned to sticky mud or turfed us out into fields. But that's where the pleasure lies. Anyone can sit in an air-conditioned coach and call himself a traveller. But cyclists know better.

We stopped when people called for photos and ate where the people ate, entering to human warmth, then a brief silence while we were inspected. Then, westerners not turning out to be so very interesting, we were accepted and welcomed.

"What is your name?

We'd tell them.

"Where are you from?"

We used to say France, but that never worked.

"From Paris," pronouncing it Paree because that's how folk knew it. We're from nowhere near Paris and we're neither of us thrilled to be taken for Parigots, but there are times to compromise.

In Dalat, we saw in the new year with a couple who invited us to celebrate with friends. They were from the travel trade, which meant they spoke good English. Believe me, it takes a lot longer than two months of cycling to learn more than a few words of Vietnamese.

"We never know what deals the government are making behind our back," a woman in her late 20s complained. "We don't know whether they're telling us everything. At the moment, the government is very unpopular."

Behind the discontent, beyond the dismay that people always feel about their leaders, are relations with China. Vietnam and its giant neighbour are exchanging words about islands which were of no interest until oil was discovered. Deals are done, or so it seems, but nobody's asked and sometimes, as the woman suggested, they're not even told.

This is a communist country but, apart from red flags and posters with exhortations ending in exclamation marks, you'd never know. On the street, it's as capitalist as Times Square.

Vietnam careered through decades of financial trouble when it tried to be a closed, people's society. It shows when you pay a bill. The best of hotels costs around 30 euros, for a multi-star place we could never have afforded at home. And in local currency? More than a million dong.

There are no coins in Vietnam. They wouldn't be worth picking up. And numbers are so enormous that people count in units of 10,000, so a bill of 50,000 dong will be presented with "That's five, please."

We rode down the coastal plain and now and then into the hills, two minor passes. The sun shone and the rain fell. We passed through half-flooded fields of fresh, green rice, and across a long, dog-legged causeway beside which passed a long, narrow wooden boat, one woman rowing and the other rhythmically banging an oar across the bows. There are as many mysteries as answers in this country.

Cycling beside the sea

We revelled in encounters and above all at the dozens of excited kids who ran from their schools to surround us whenever we stopped. Passing a school in Vietnam has much the consequence of banging your fist on a hive.

But how we were frustrated by not being able to talk. There's limited satisfaction in exchanging names and ages and learning that the Vietnamese for selfie is indeed selfie.

I'd love to speak all the languages of the world. For two months I longed to speak Vietnamese. For all their odd ways, and for all their driving is less steering than sticking a hand on the hooter and leaving it there, the Vietnamese are lovely people. Happy people.

And oh how much we longed to talk with them.