Major Taylor’s 1928 Autobiography Speaks to Us through the Decades

By Peter Joffre Nye

Author Peter Joffre Nye's latest work is his updated and revised second edition of Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing. It is available in hardcover and Kindle eBook.

If bicycle racing matters to you, you will love this book. Hearts of Lions is a colorful, exciting, classic work on the art of bicycle racing over 140 years against a backdrop of social, political, and technical changes.

Just click on the Amazon link to the right to get your copy of this terrific book.

Also on this site is Mr. Nye's story of one of cycling's toughest-ever racers, Reggie McNamara. McNamara won over 700 races and was one of the greatest-ever six-day racers. Oh, and there's more! Nye's story of Joseph Magnani, the Illinois rider who challenged Coppi and Bartali.

Enjoy!

Peter Joffre Nye Writes:

Of the many thousands of American bicycle racers competing since national championships began in 1883, Marshal (Major) Taylor stands out as the subject of more biographies and magazine features than anyone who ever swung a leg over the top tube to ride. He raced as the rare Black professional during unchecked Jim Crow racial segregation against white rivals in events presided over by white judges and in front of mostly white audiences before the great migration of Blacks leaving Southern plantations and farms to work in factories in the North. He beat every top rider at least twice to win three straight national titles from 1898 to 1900, and he captured the 1899 world professional sprint crown in Montreal, Canada.

Maybe the first magazine cover of a Black athlete—an exclusive in Paris, the City of Light, in 1901.

Taylor stood five feet seven, average for men of his generation, but he exerted an oversized influence by setting more than twenty world records when bicycles with steel diamond-shaped frames and both wheels the same size created the world’s first modern sport. Basketball was spreading from one college campus to the next around New England after its invention in Springfield College in Massachusetts. Football mooned in the shallows as a niche pastime alongside soccer and badminton. Like horse racing, bicycle races attracted bigger audiences, more press coverage, and greater money from the Atlantic to the Pacific than Major League Baseball.

Major Taylor on the pole against Dutchman Jaap Eden, Buffalo Athletic Field, August 24th, 1897

Taylor specialized in short, fast events on tracks when sprinters with chain lightning in their legs filled grandstands like tenors did for opera houses. City speed limits were 10 miles an hour in deference to the 18 million horses and mules dominating roads before the advent of automobiles and motorcycles. Bike racers dazzled audiences by cruising at 25 mph and dashing over 35 mph.

Born and bred on the west side of Indianapolis, Taylor turned pro at eighteen in 1896, the year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the landmark case Plessy v. Ferguson that codified the principle of “separate but equal” in all public facilities. Douglas A. Blackmon, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Slavery by Another Name, writes the decision “legitimized the contemptuous attitudes of whites.”

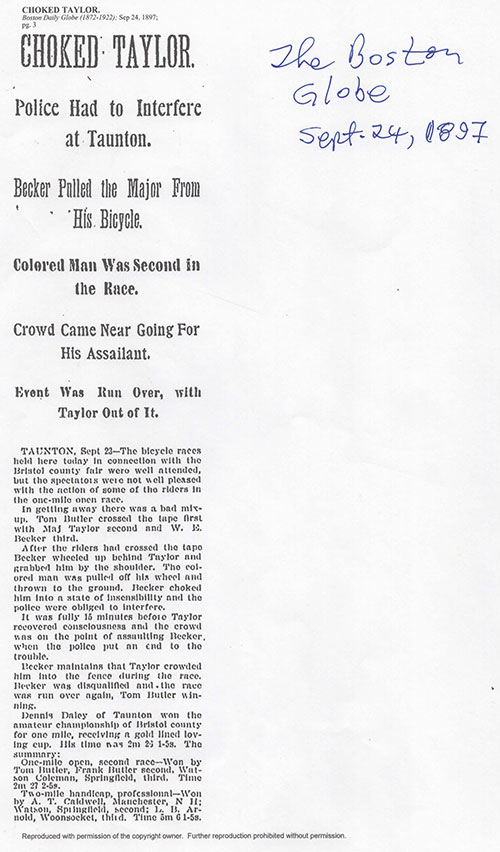

Envious rivals didn’t hesitate to shove Taylor into the infield or try to knock him down. In September 1897 at the Bristol County Fair in Taunton, Massachusetts, Taylor nipped W.E. Becker for second place in the one-miler on a dirt track. Becker, the national five-mile champion, wheeled up behind Taylor and seized his shoulder.

“The colored man was pulled off his wheel and thrown to the ground,” reported the Boston Globe. “Becker choked him into a state of insensibility.” The report added: “It was fully 15 minutes before Taylor recovered consciousness and the crowd was on the point of assaulting Becker when the police put an end to the trouble.”

Major Taylor, Owen (Old Kentucky) Kimble of Louisville KY, Tom Cooper of Detroit, Arthur (The Blond Adonis) Gardiner of Chicago, and Eddie (The Cannon) Bald of Buffalo. On the new Buffalo Athletic Field, a quarter-mile banked cement track, September 27, 1897. Photo credit: Collection of the Buffalo History Museum. Goldome/Nagle photograph collection.

Taylor avoided getting trapped into a “pocket” in races. When he drafted behind the leader hugging the inside lane, a rider conspiring against him would slide next to his right side. An accomplice sat on Taylor’s rear wheel to hold him in the pocket. A fourth would swing around wide headed for victory and afterward to split the prize money with his cohorts. Taylor escaped hundreds of times by swerving his handlebars hard and slapping his front wheel against the rear wheel directly ahead of him, invariably frightening the rider ahead, causing him to veer out enough for Taylor to kick through to win.

Major Taylor rode as an early aero advocate with deep drops to lower his back profile. Shown here as a rising star at eighteen in 1896 in the studio of George H. Van Norman in Springfield MA. Photo courtesy of the Lyman & Merrie Wood Museum of Springfield History in Springfield MA.

What motivated him to persist against aggressive opposition was his love of the sport and prize money. No state or federal taxes were deducted; dollar bills were one-third larger than today—winners took home a fist full of cash, sometimes $1,000 in a day, now worth $35,000.

Taylor’s fellow Hoosier, Frank Kramer of Evansville, related in a 1916 issue of Motor Cycle Illustrated how Taylor persuaded him to turn pro after Kramer won his second national amateur championship in 1899. They were passengers in a train car following a race program in Philadelphia when Taylor joined him as he chatted with a friend. Taylor had won two races that day and brandished an impressive roll of bills. Kramer, two years younger, described the roll as big enough “to trip up an elephant.” He turned pro for the 1900 season.

In 1900 Major Taylor had a sponsorship with Iver Johnson Bicycles. He was paid $1,000 a year, $35,000 in today's money.

Taylor raced to show audiences, newspaper and magazine reporters, event organizers, and opponents that he could battle wheel to wheel and beat his competiton in a fair contest. Retired National Basketball Association player Darnel Hillman, a six-foot nine-inch African American who played for the Indiana Pacers, told me that pioneer Black athletes, like Taylor and Major League Baseball’s Jackie Robinson, who integrated the Brooklyn Dodgers (predecessor to the Los Angeles Dodgers) in 1947, suffered tougher physical demands and mental pressures than whites.

“Trailblazers are on their own,” observed Hillman, nicknamed “Doctor Dunk” for an extraordinary vertical jump that helped him win the prestigious 1977 NBA Slam-Dunk Contest. “When one steps up, he steps up for all. It’s very tough for trailblazers. They are on their own, and it takes a commitment because they are on their own. Major Taylor had made a commitment to achievement and accomplishment and to winning.”

Reports of Taylor’s prowess telegraphed across the Atlantic. Paris track promoters and French cycle makers offered him $10,000—worth $350,000 today—to come. Taylor, a devout Baptist, never raced on Sundays. He turned down the offer because it called for Sunday racing. The Brooklyn Eagle published a headline declaring, “Major Taylor Refuses $10,000: The Colored Cyclist Declines to Race on Sunday.” Many other papers ran similar reports.

Taylor refuses $10,000.

Taylor won three national titles during a contentious turf battle between the staid League of American Wheelmen, founded in 1880, and the upstart National Cycling Association. The LAW sought to keep Sunday as a day of rest and regarded cash prizes as sullying the sport; the NCA pushed for Sunday racing and bigger purses. Pros began deserting LAW’s events for NCA races. Taylor remained loyal to the LAW and won its 1898 and 1899 national titles. Each season ended with two different national champions.

In early 1900, the LAW capitulated and withdrew from sanctioning races. Taylor prevailed in the season-long NCA competitions for points that gave him his third title. He out classed runner-up Kramer in their last match race. Taylor reigned as the undisputed national sprint champion. White riders boasted they would work in concert to thwart him the next year.

Taylor finally accepted an offer he couldn’t refuse from a Paris consortium: a $5,000 appearance fee, worth about $170,000 today, and no Sunday racing. All the prize money and bonuses he won for setting records was his to keep. He shipped out in late February 1901.

To stimulate ticket sales in Paris, the city’s weekly sports tabloid, La Vie au Grand Air (Outside), splashed Taylor’s image across its front page—likely the first cover featuring a Black athlete. He looks straight ahead, eyes focused, back bent low, hands gripping dropped handlebars, elbows tucked at his sides, ready to spring off the page. The headline shouts: Le célébre sprinter noir (The famed Black sprinter).

He competed on cement and board tracks filled to standing-room-only crowds in Paris and fifteen other cities, most of them national capitals across the Continent. He scored an impressive forty-two firsts, eleven seconds, three thirds, and one forth.

Taylor returned home and joined the racing circuit for points counting toward the 1901 national title. His campaign abroad paid well but left him behind in points. He couldn’t overcome the deficit in his quest for another title. Kramer became the unspoken White Hope and won the national championships that year and for the next fifteen years.

Paris promoters treated Taylor as a star and invited him back again in 1902. For most of the decade, he did his best racing overseas—like three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond. Taylor’s box office success on the Continent led to invitations with bigger appearance fees to race the 1903 and 1904 seasons in Australia and New Zealand. He became the first African-American international superstar athlete.

By the time Taylor retired from competition, at thirty-two in 1910, he filled nine scrapbooks chronicling his career. Maintaining a scrapbook proved too much trouble for most pros. Once the race program closed, riders collected their prize money, managers packed bikes in wooden cases, and they fled to the train station to check bike cases in the luggage car. Riders and managers sat in the belly of train cars swaying on steel rails up to 40 mph to the next destination, the next track. Bike cases had ENTERTAINER painted in black, front and back, to inform baggage handlers to take care they traveled with their owner because, as entertainers say, the show goes on.

Taylor had an eye toward his posterity. He routinely picked up the latest edition of local newspapers at the train station for coverage of his events and later pasted the accounts, story by story, into one scrapbook after another.

Major Taylor mural in downtown Indianapolis. Photo: Joe Vondersaar/SRAM

In the mid-1920s, American popular culture and the economy had transformed in ways beyond anything Taylor could have imagined in his youth. The smart set that had propelled cycling in the 1890s took up other hobbies. The Eastman Kodak Company had introduced low-cost Brownie cameras, which enjoyed huge commercial success. Golf, tennis, and swimming grew in popularity across urban communities. Most of the 300 bicycle manufacturers in 1900 merged or went bust as demand plummeted and manufacturers shifted into producing cars. In 1909, America had 290 different makes of cars produced in 145 cities in twenty-four states.

A rival from Taylor’s his first bike race, Walter Marmon, was presiding over the Marmon Motor Car Company of Indianapolis, boasting of the fastest passenger cars on the market. Taylor had won the ten-miler at age thirteen in 1892, six seconds ahead of second place Marmon. In 1911, the Marmon Wasp gained motorsports immortality for winning the first Indianapolis 500.

The sports world expanded and overtook cycling. All the tracks Taylor rode on had disappeared. Basketball caught on with college campuses nationwide and in public schools. His daughter and only child, Sydney, born when he raced in Sydney, Australia in 1904, grew up in a two-story Queen Anne home Worcester, Massachusetts. She stood five feet three and played varsity basketball for South High. She left home for college, graduating in 1925 with a physical education degree from West Virginia State University.

Around that time, Taylor began his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success against Great Odds. In 1928 he published it at his own expense.

Taylor died in Chicago of heart congestion in June 1932, age fifty-three. Baseball great Jackie Robinson, who integrated Major League Baseball, died in 1972, also of heart disease at age fifty-three.

Doctor Bruce Boros, a cardiologist in Key West, Florida, told me that prolonged stress may have triggered the hormone cortisol, linked to causing heart disease, stroke, and depression. “Sleep deprivation, anxiety, and stress elevate levels of cortisol,” he said. “Hypertension in African Americans of that era was severely underdiagnosed for many reasons and could have been a huge factor” in the deaths of Taylor and Robinson.

* * *

Sydney Taylor Brown represented her father in 1989 at his posthumous induction into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame, in Somerville, New Jersey (now in Davis, California). She retained the poise at eighty-five of one who grew up in comfort, with a maid and a cook. She had soft brown skin and was well proportioned, like a gymnast, someone who could pull on clothes straight from the rack and they fit as though custom made. She looked sharp in a tweed jacket, flashed a warm smile when speaking, had neatly coiffed salt-and-pepper hair, and left the scent of Channel No. 5 trailing in her wake.

She lived in Pittsburgh and had retired in the 1970s from working for the Veterans Administration as a psychiatric social worker. Several people at the induction ceremony expressed surprise in learning that Taylor and his wife, Daisy Victoria Taylor, had a daughter. Sydney relished meeting people wanting to learn more about her father.

Sydney told me over dinner that he had mined the scrapbooks to compose his book. (In 1988 she donated her father’s scrapbooks to the Indiana State Museum.) He dictated the manuscript to a local business-school student, quoting at length from published accounts and spicing the narrative with his asides. His first-person account, the only one from his generation, provides a matchless perspective on the early years of the sport, which swiftly circled the globe. Cycling was included in the modern revival of the Olympics in 1896 in Athens, Greece, and endures as one of five sports in every Olympics.

His autobiography captures a pivotal day for the sport and industry in 1892. He was in a big meet in Peoria, Illinois, on a dirt half-mile oval, to ride in the division for boys sixteen and under. “Peoria was the Mecca of bicycle racing in those days,” he wrote.

Taylor saw William Laurie of England on a bicycle equipped with novel Dunlop pneumatic tires. Laurie was seen before his events on the infield pumping up his tires, which must have amused spectators, accustomed to seeing bicycles with hard-rubber tires, like those common today on grocery cart wheels. Word flashed around grandstand and bleachers that his tires came from Dublin, Ireland and he filled them with air from his pump—arousing ridicule.

Laurie’s pneumatics were twice as wide as hard-rubber tires and allowed his bicycle to glide over the dirt surface. Hard-rubber tires sank a little for drag. Riders on them and spectators alike watched Laurie pull away with every pedal stroke. “Hoots and jeers greeted Laurie throughout the afternoon as he blazed the trail for the use of pneumatic ties, which revolutionized bicycle racing, and the manufacture of bicycles simultaneously,” Taylor wrote.

Some pros refused to cross the “color line.” He cited three-time national champion Eddie (The Cannon) Bald. Andrew Ritchie in Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer said that Bald had no prejudice against him. Taylor wrote that Bald complained about the volume of letters he received from fans scolding him for recognizing a Black man.

Recounting when W.E. Becker had choked him till the police intervened, Taylor wrote judges disqualified Becker and ordered the race to be re-run. “I was too badly injured to start,” he said. Becker was suspended for a couple of days and fined $50, paid for by white riders.

Taylor reprints a booklet by Paris journalists Paul Hamelle and Robert Coquelle, Major Taylor, the King of the Cycle, His Appearance, and Career. They said his skin color, “which had always been a serious drawback for him in America, was already a benefit to him in this country.” Upon Taylor’s arrival in Cherbourg, in northern France, and in Paris, the Frenchmen described “a rushing of reporters and photographers. For one solid week, Taylor was the man of the hour. There were races and staged both on and off the track and bazars were held.”

Taylor’s voice speaks through decades. He provides a graphic description of the sport as he knew it in the United States, on the Continent, and in Australia. He describes domestic and foreign opponents on the day he had faced them, what it was like pedaling around the steeply banked wooden tracks or longer sloping cement ovals, how spectators reacted when he, and rivals, made the decisive move that led to victory and a rewarding payday.

His hardcover book of 431 pages runs ninety-four chapters tallied in Roman numerals, from Chapter I to Chapter XCIV. He inserted dozens of photos of himself, fellow pros, and foreign champions. The images capture his rivals on three continents, forever young.

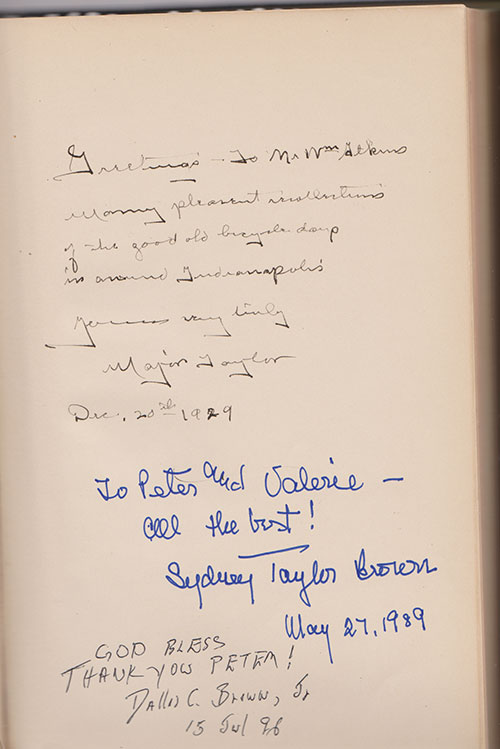

Major Taylor 1929 signed autobiography.

Michael Kranish writes in The World’s Fastest Man: The Extraordinary Life of Cyclist Major Taylor, America’s First Black Sports Hero that Taylor was the grandson of slaves; his father, Gilbert, fought in the Union Army, in a segregated unit the 122nd US Colored Troops, on the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia, the Confederacy’s capital.

Taylor acknowledges years of bitter feelings and malicious practices he endured from some white riders, their friends, and sympathizers. Yet he remains evenhanded throughout.

Chris Sinsabaugh, who made his bones as a reporter on the 1890s Chicago weekly Bearings: The Cycling Authority of America, rose to editor of Automotive News in Detroit. His 1940 memoir, Who Me? Forty Years of the Automobile History, reports Taylor knocked on doors to hand-sell his book to old friends.

A fellow pro, Walter Bardgett of Buffalo, the victim of a career-ending crash, became bicycle editor of American Bicyclist & Motorcyclist and plugged Taylor’s book for sale out of his New York office. He filled orders by adding an extra copy or two to reduce his inventory.

Taylor signed a copy on December 20, 1928 to William Atkins: “Many pleasant recollections of the good old bicycle days in around Indianapolis.” That book wound up in the early 1960s in Johnson’s Bookstore, a landmark on Main Street in downtown Springfield, Massachusetts, where my father plucked it from a jumble of used books for fifty cents.

How Taylor’s autographed copy traveled five states to Johnson’s Bookstore testifies to the attention that the store devoted to books—new and old—and Taylor’s reputation. The book feels heavier in my hand than most contemporary books of comparable page count. A box holding thirty copies would weigh more than forty pounds, a heavy load to lug around and hand-sell. His print run of some 2,000 copies must have weighed more than a ton.

I confess that my initial foray into reading my father’s copy left me bewildered. The names of Taylor’s contemporaries were lost on me, however famous they were in his time. You’d think that Arthur Gardiner of Chicago, nicknamed “The Blond Adonis,” would sound familiar to bike racers the way film buffs know of Rudolph Valentino. But history is a brutal editor.

Over the years, I’ve re-read Taylor’s book while researching stacks of brittle periodicals at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C., and its nearby James Madison Building Memorial Library housing newspapers on microfilm. Taylor provides an invaluable framework of the sport, its players in America and more than a dozen other countries where he rubbed wheels and bumped elbows against titleholders on their home tracks before SRO crowds.

“I always gave the best that was in me,” he wrote. “Life is too short for a man to hold bitterness in his heart, and that is why I have no feeling against anybody.” He added: “I have also enjoyed the friendship of countless thousands of white men whom I class as among my closest friends.”

He was candid in what he saw in the future: “There will always be that dreaded monster prejudice to do extra battle against men because of their color.”

Copies of Taylor’s book come up for sale on eBay. It is also available in digital format:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015010834771&view=1up&seq=11.

(Peter Joffre Nye is author of the updated second edition of Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing, available from the University of Nebraska Press, www.nebraskapress.unl.edu.)